The Abysmal Depths of Chess

A few months ago, I advised a student of around 2000 strength to try to analyse one complicated game deeply and carefully. I asked him to keep on honing and revising his findings until he felt confident that I wouldn’t find any major mistakes in his analysis. I encouraged him not to use analysis engines until he had given it his best effort. He was not allowed to make generalizations about the position and not allowed to stop with the assessment that the position was 'unclear' unless he could demonstrate the effort he had made to find clarity. He is a diligent student and keen to improve, but looking at a complicated game in depth until he understood it move by move, variation by variation, proved to be too much for him. He devoted a few study sessions to this task, a couple of hours at a time, but he came back to me and said that he was 'scared' to do any more. Whenever he tried to look at the position without prejudices he felt 'lost' and 'helpless' and this gave rise to a sense of despair. It was clear to me that he had glimpsed what Nabokov called "the abysmal depths of chess".Jonathan Rowson, Chess for Zebras

I’m guessing that if you’re reading this you know exactly what Nabokov was getting at. If you’re lucky enough for that not to be the case then I suggest you get hold of one of the training books that Artur Yusupov thinks is appropriate for your playing strength. You’ll be on the same page as the rest of us soon enough.

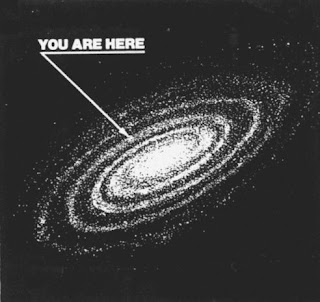

Chess is a complex game, yes, but it’s much so much more than that. It’s Douglas Adams’ Total Perspective Vortex. Even a glimpse into the depths the game can reach can be impossible for a human mind to handle. Fear and despair being the result. Seligman’s Learned Helplessness is a far from a theoretical concept for chess players and very much an occupational hazard. Abysmal, indeed.

Yusupov, incidentally, is an equal opportunities crusher of chess souls. Happy to destroy the minds of all comers regardless of rating. Here’s Rowson talking about his experience of training with the old Russian.

This consisted almost entirely of attempting to solve exercises that he knew well. The training exercises had definite answers, but they also resembled real positions so if I deviated from the answers, Yusupov would put down his book of answers and I had to deal with the man himself! This took place over the course of give days at Artur’s house in Germany. I enjoyed the hospitality of the Yusupov family, but my ego has never had such a systematic pounding before or since. I imagine we looked at about 30 different difficult positions, and in most cases I got the first few moves right only to slip up towards the end. Almost never did I get the solution right from start to finish. It made me feel like a very weak player.

Rowson was a Grandmaster at the time. Still, rather than finding it thoroughly depressing, he thinks that exposure to the full complexity of chess isn’t a bad thing per se. For Rowson this kind of emotional beating goes beyond even being a positive. He feels this kind of experience is essential for anyone wanting to improve. You just have to find a way to do it in a controlled and supported way.

I think of the Beat the Masters puzzles in exactly this context. So far, just like Rowson battling through Yusupov’s problems, I invariably make mistakes a few moves into my analysis even when I choose the right first move - and that’s not a given. Sometimes, I feel completely unable to get a grip on a position and feel like a total beginner.

The important thing, though, is just to keep going. For Rowson training like this also has the benefit of 'concentration training'.

… the main thing is to get into the habit of sitting down, selecting a problem, setting it up, setting the clock, thinking, stopping, comparing your analysis with the source analysis … and keep doing this. It will be hard, and you will not really be 'learning’ anything through this. But, as I’ve said before, chess is about skill - what you needs is not 'know-that' but 'know-how'.

So, yes, Nabokov was on to something. Even so, you can’t learn to swim without one day heading out into the deep water. That’s just the way it is.

But what are the right approach or steps an adult can take to improve chess? How do you know how

ReplyDeleteQ: "How do you know how"?

DeleteA Do you mean how do *I* know, or how does a person in general know?

What are the right steps? A detailed answer to the question would need me to know more about you - how old are you? how long have you been playing? what standard are you now? what are study are you doing now? how much time do you have available etc etc.

But the general answer is going to be true for everybody anyway. It’s just a question of how you vary the details. To improve you:-

study a chess position,

you decide on what you would do,

you get feedback on your thoughts (from a book or a magazine article or an engine or a coach)

you look for patterns in your thinking - things you do well (do more of that), typical mistakes you make (do less of that),

you do it all again. A lot.